Among the many skills we must learn as doctors in training, breaking bad news is one of the hardest. It’s a skill we’re expected to master, yet it’s one we secretly hope we’ll never need. The truth is—we don’t want to face it at all.

In a field often filled with sugar and spice, where we rewind the cycle of life like a beautiful merry-go-round, we also stand face-to-face with death. And what makes it even heavier is that it’s never abstract—it’s someone’s loved one, sometimes one, sometimes both. And it’s almost always unexpected.

A week ago, I was sitting in the OPD office, seeing patients one after another. Then came a couple, eager and glowing, excited to meet the tiny life just beginning inside her womb—a pregnancy only a few weeks into the first trimester.

But as I moved the probe and searched, I couldn’t find what I should have: a heartbeat. In that moment, it wasn’t silence that filled the room, but the deafening thud of my own heart, quivering as I realized something was wrong.

Being a doctor in training, I had to refer her to radiology for confirmation. Yet what broke me the most wasn’t the absence of sound on the monitor—it was the husband’s steady hand on his wife, gently assuring her that everything would be fine, whispering prayers that carried more hope than certainty.

I spent the rest of the clinic with that couple lingering in my mind. Questions kept drilling in, pressing harder until they gave me a headache. As I sat there covering the OPD alone, I couldn’t stop wondering—would I be the one to break the bad news? And if so, was I ready?

The truth is, I wasn’t sure. The last time I had ‘practiced’ breaking bad news, it wasn’t in real life—it was during a mock exam. This, however, was no simulation. This was a moment that could alter the course of someone’s world.

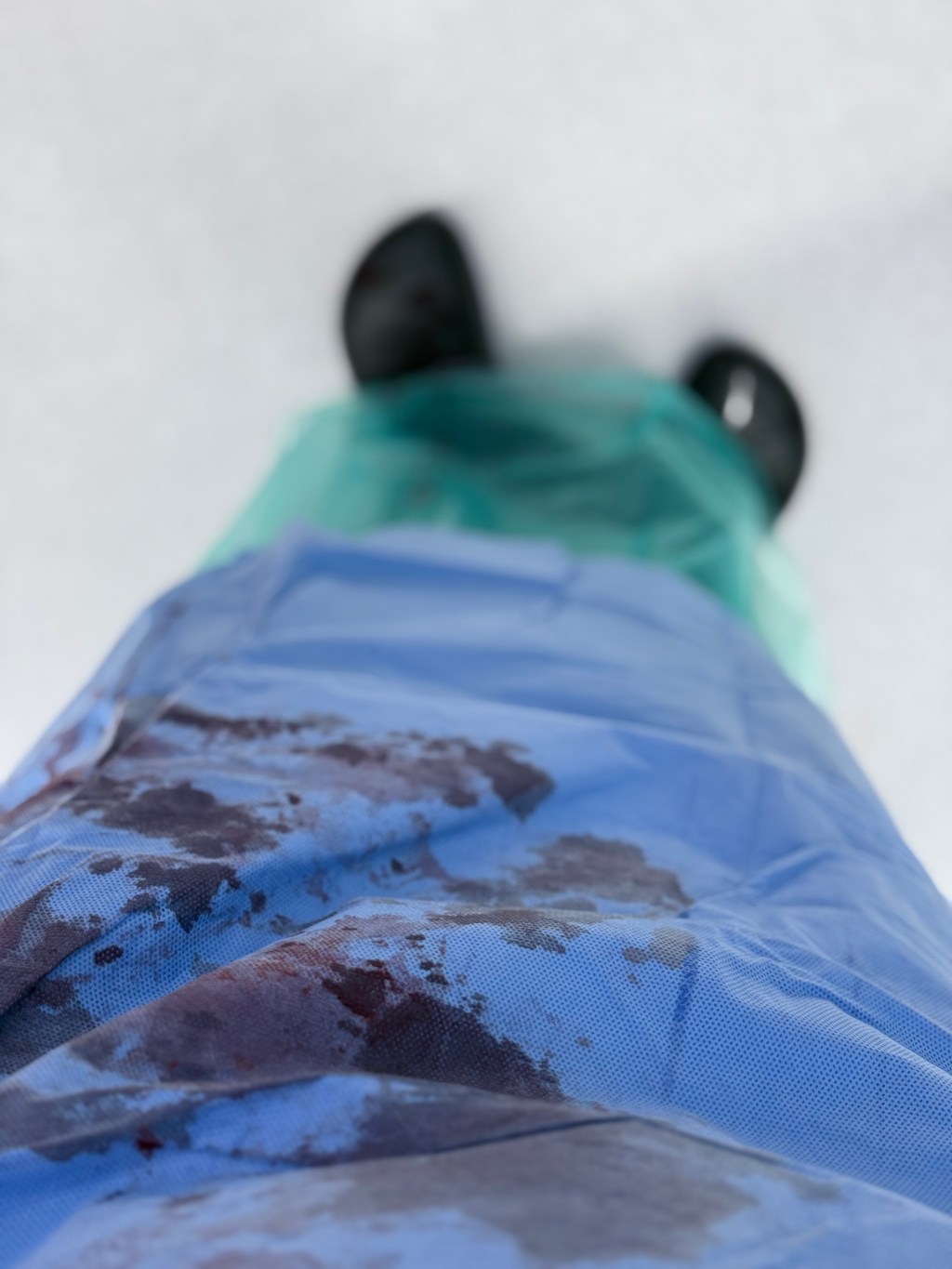

A knock on the door, and there they were. My heart clenched as I reached for the report. The words stared back at me—‘No cardiac activity. Impression: missed abortion.’ I read it over and over, almost hoping the letters would rearrange themselves into something else.

I had cared for women with the same diagnosis before, been part of their management and follow-up. But never had I been the one to give it a name—to place the label that could shatter a couple’s world.

I swallowed hard, buying a few seconds before the words finally left my lips. I did what I had been taught to do as a health provider, clinging to the structure we were trained with. Somewhere deep inside, I sensed they had already prepared themselves. Perhaps that made it a little easier—or maybe harder.

There were no tears, at least not in that moment. But there was something heavier—the quiet agony in her voice when she asked me, ‘What caused this?’

It is moments like these that shape us as women, and as doctors. On that day, I realized what so many women quietly carry—the weight of miscarriages, the loss of fertility after unwanted hysterectomies, the heartbreak of a fetal demise when it is least expected.

I realized, too, how strong women are. How much power lies in their ability to endure, to rise, and to keep moving despite it all. This field grants me the privilege of witnessing both the beauty and the tragedy of womanhood—life’s first cries, and sometimes, its deepest silences.

It also grants me the chance to offer something—however small—in those moments: comfort, guidance, and presence. Because sometimes, words alone are not enough, but presence can be everything.

In the end, medicine teaches us this truth: as someone once said, “we may not always heal, but we can always hold space.”

Leave a comment